They come in small groups, families hand in hand, grandparents too, young lads and lasses, walking along the dusty rural lane between the ancient drystone walls with one objective: to reach the well.

On the last Sunday in August, at the end of a hot, dry summer, the Spotlight team made our way to the little well just outside the hamlet of Baláfia - in San Lorenzo - to witness one of Ibiza’s most cherished traditions: the ball pagès. Taking place beside the spring, it is a way of revering the source of life - water - celebrating together, playing games and enacting an ageless courtship ritual.

Though we’d given no prior warning of our arrival, the local people gave us a heartwarming welcome.

Around 100 residents of the area - including some from other parts of the island - milled around the tiny area. All the conditions were perfect since the town council of San Juan had recently repainted the well and even resurfaced the patch of ground before it so that the colla (the local dance association) could perform on a smoother surface and the women would not drag their dresses in the dust.

A long table to the side was festooned with a smorgasbord of typical tasty homemade treats à la Ibiza: coca, tortilla, empanadas, flaó and more. The gentle sound of glasses clinking, conversation (almost all Ibicencan, barely any Spanish and no English at all) and laughter fills the air.

The female compere takes the mic and a hush comes over the crowd. Two by two, the dancers step forward.

The males, adults and teenagers, are dressed in their simple garb: billowing white tunics with high collars, a cravat, loose-fitting pants and a vibrant red or purple cotton sash (sa faixa) wound tightly around their waists.

The women wear their customary working clothes: a dark-coloured, embroidered cape (el mantó), and layers (up to eight!) of skirts. Their hair is braided and tied back with a ribbon. Both they and the men wear the rustic handmade footwear known as espardenyes (what we call espadrilles).

Set to the droning sound of drums, pipes (els xeremies) and castanets, the dances are short and lively.

The women, their faces cast down in modesty, weave figure-of-eight patterns using tiny, dainty steps. Their feet invisible to onlookers, it appears as if they float on air.

Meanwhile, the men circle around their partner, hopping, jumping, kicking high in the air, and clicking their castanets. Eager and intent, they watch their partner closely, searching for a sign of approval.

Suddenly, he stops and kneels before her, looking up in earnest. She curtseyes demurely and withdraws. New duos form, young and old, tiny tots and village elders, well trained (once a week all year) and first-timers. The dance of time goes on.

Half an hour passes, the light fades and the half moon appears through the clouds above. The night feels intimate, ancestral and alive. It’s the turn of the children, who cluster together to play an ancient game known as la granera that involves passing a broom around (like musical chairs). When the music finally ceases, one sole child is left; she receives her prize then hurries back to mum and dad, beaming with joy.

In the break, we return to the ‘bar’ in search of refreshment. We get into conversation with one of the elders. He tells us more about the meaning of the ritual, its roots way back in pagan times. It’s a way of worshipping the life-giving properties of the rain that nourishes the crops in summer. An age-old custom, it’s a shared experience where the villagers meet, carouse and celebrate another harvest together. A reminder that here at least, in this corner of the White Isle, community lives on.

And much to our surprise and delight, he tells us of the younger generation’s budding interest and involvement in such features of heritage.

More activities ensue: guess the weight of the wicker basket laden with produce, buy a raffle ticket for prizes donated by local businesses: a hamper of fresh fruit and vegetables, bottles of wine, chocolates, a change of oil at the garage, dinner at a local restaurant.

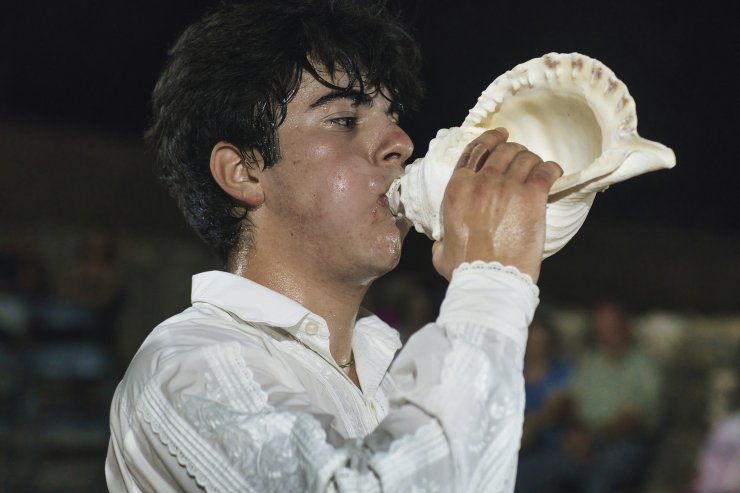

Then it is time for the singing contest to see who can perform best the ancient cry that once echoed across the fields, the ‘UC’.

The competition is announced by blowing a shell, which sets the tone with its inimitable echo.

A long wavering shout, the UC is an unforgettable, haunting sound. In the past, it was mainly used by women (las pagesas) to express joy and sorrow, to call someone home, announce vital news or give warning.

The very essence of the island’s soul, it is rarely heard today outside of weddings, festivals and the ball pagès itself. The men and women step up, some shy, some brimming with confidence. After several rounds, a winner is chosen by the jury, who sit with their backs to the singers.

A final session of more informal dancing commences. At around 11pm, the evening comes to an end. The organisers pack up their kit and clear the table of the empty plates. Attendees bid farewell to one another, then wander off into the balmy late summer night, homeward bound.

The month-long patron saint festivities of San Lorenzo conclude and the rite of autumn is over until next year. May the rains come, may we dance, live and love anew.

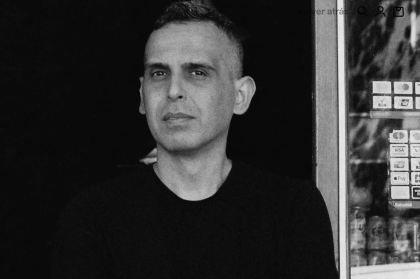

Photography by La Skimal